Belladonna

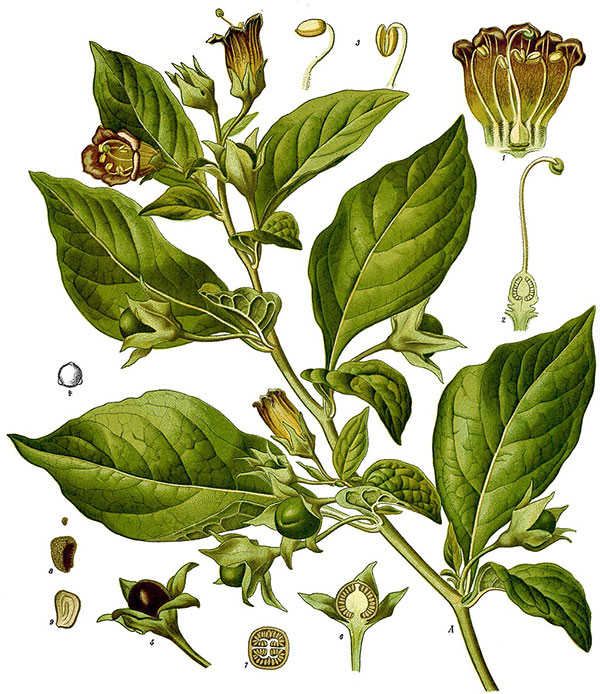

Belladonna (Atropa belladonna)Illustration - Köhlers Medizinal-Pflanzen (1887) (PD)

Background & General Info

Deadly nightshade, Atropa belladonna or simply belladonna, is a notoriously poisonous medicinal plant that globally rose to pharmacological fame because of its leaves and berries, from which the anticholinergic drug atropine was isolated for the first time. [1] Its roots, leaves, and fruits also contain hyoscyamine and scopolamine, two important alkaloids that are used medicinally to control symptoms of gastrointestinal disorders and to treat motion sickness and postoperative nausea, respectively. [2] Its scientific name was derived by Linnaeus from Atropos, one of the Three Fates in Greek mythology who cuts the “threads” of mortals, ending their life. [1]

Commonly found in temperate quarries and waste ground of Europe, North Africa, and Western Asia as a native species, this herbaceous plant is so dangerous because of its tropane alkaloids that ingestion of 10 berries would be life-threatening to adults (2–3 berries for children). [2] Notwithstanding belladonna’s sinister repute, it has several positive properties and pharmaceutical and therapeutic applications.

Belladonna - Botany

Belladonna is a perennial bushy herb with bell-shaped greenish-purple flowers and broad, oval, dark green leaves. The leaves come in uneven pairs, with one leaf of a pair being much larger than the other, and the flowers develop solitarily in the leaves’ axils, blossoming between June and September. Belladonna bears globular green berries that ripen with a shiny black color; these berries produce ink-like, sweet juice and are consumed by different animals, which in turn help scatter the seeds through their droppings. When full grown, Belladonna can reach a height of up to 2 meters and possesses a purplish stem thickly covered by short, fine hairs. [3]

Belladonna - History & Traditional Use

The dual role of belladonna as both a medicine and a poison has long intertwined in the history of its use. For instance, surgeons during the Middle Ages used the plant as an anesthetic but the ancient Romans employed it as a poison for murder, usually smearing tips of arrows or weapons with belladonna. [4] In 1867, von Bezold demonstrated the ability of belladonna’s atropine to block the heart-related effects of vagal stimulation, whereas Sir James Mackenzie (1853–1925) revealed its ability to revert partial heart block following his studies of its effect on heart rate of digitalized patients in atrial fibrillation. When it was introduced in coronary care units, the compound became a leading drug of choice for the treatment of bradycardia and heart block after myocardial infarction. [1]

Some of the historical or theoretical uses of belladonna still remain to be supported by unclear or conflicting scientific evidence, and its indications include abnormal menstrual bleeding, acute inflammation, anxiety, arthritis, diarrhea, colds, earache, encephalitis, fever, flu, gout, hay fever, hemorrhoids, motion sickness, mumps, muscle and joint pain, urinary retention, warts, nausea and vomiting during pregnancy, and whooping cough, among others. [5]

Belladonna - Herbal Uses

For several centuries, Belladonna has established itself as an herb used for various indications, including headache, menstrual symptoms, peptic ulcer disease, inflammation, and motion sickness. [5] When in combination with phenobarbital, belladonna alkaloids are prescribed as treatment of cramping and spasms in the stomach and intestines, especially for stomach ulcers. [6] Findings from preliminary studies proposed the possible efficacy of belladonna to manage symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome when used in combination with barbiturates. [5] Preparations of Atropa belladonna are also used in human phytotherapy, mostly against spasms and colic-like pains in the gastrointestinal and biliary tracts, although only standardized belladonna preparations such as belladonnae pulvis normatus that contain approximately 0.28% to 0.32% total alkaloids (i.e., 280 to 320 mg/100g) can be used therapeutically and safely. [7]

Belladonna - Constituents / Active Components

All parts of Belladonna contain significant amounts of tropane alkaloids, with the roots, leaves, stalks, flowers, ripe berries, and seeds having 1.3%, 1.2%, 0.65%, 0.6%, 0.7%, and 0.4% of these alkaloids. The roots are clearly the most poisonous, especially at the end of the vegetation phase, and have an alkaloid content of 0.2% to 1.2%. [7][8]

According to a 1998 summary report by the Committee for Veterinary Medicinal Products of the European Agency for the Evaluation of Medicinal Products, the total content of pharmacologically active tropane alkaloids of the overground parts of belladonna is 0.2% to 2.0% in dry matter, with average values ranging from 0.3% to 0.5%. (S)-Hyoscyamine is considered the main alkaloid of the total alkaloid complex of belladonna, with an 87.6% composition in the leaves and 68.7% in the roots. Other alkaloids in the leaves include apoatropine (or atropamine, 6.7%), tropine (3%), scopolamine (1.9%), aposcopolamine (0.5%), 3-α-phenyl-acetoxytropane (0.3%), and tropinone (0.2%). [7]

Belladonna - Medicinal / Scientific Research

Wound Healing:

Findings of a 2009 study demonstrated the positive effects of belladonna water extract on early phases of skin wound healing in male Sprague-Dawley rats subjected to two parallel full-thickness skin incisions on their back. In the in vivo experiments, the wounds in rats treated with belladonna water extract were characterized by shortened inflammatory process, hastened collagen formation, and significantly increased stiffness in comparison with control tissues. In the in vitro assessment on the other hand, control keratinocytes were free of cytokeratin 19 and samples treated with the highest concentration of belladonna extract expressed CK19. Furthermore, the extract at all concentrations stimulated the proliferation of human umbilical vein endothelial cells and, even at the lowest tested concentration, augmented the growth of fibroblasts (cells of connective tissues that play an active role in wound healing). [9]

Atropine:

Atropine is the chief alkaloid found in mature fruits of belladonna, comprising around 98%; each berry of belladonna is estimated to contain 2 mg of atropine. [10] It is an anticholinergic and antimuscarinic drug that causes pupil dilation, increases heart rate, and increases secretion of saliva. Since atropine boosts the heart rate and improves the atrioventricular conduction via blockade of parasympathetic influences on the heart, it can be used in the management of patients with bradycardia. [11] Atropine eye drops are extensively used in clinical practice, especially in Asian countries, as a long-term beneficial treatment of myopia (or nearsightedness) despite atropine’s clear limitations and complications. According to recent reports, a low concentration of atropine is effective for myopia control and has fewer severe side effects. [12]

Contraindications, Interactions, and Safety

WARNING! This plant is very poisonous. Because of its physical resemblance to other edible berries such as blackcurrants and blueberries, Belladonna poses a risk of poisoning to children. [2] Acute belladonna poisoning is a severe condition that primarily requires symptomatic treatment such as gastrointestinal decontamination with activated charcoal and/or administration of physostigmine as antidote. [2] A vast amount of data on the adverse effects and toxicity of belladonna associated predominantly with the plant’s anticholinergic actions can be found in the literature, and the acute toxicity of the plant and its preparations is linked to the alkaloids atropine and hyoscyamine. [5]

Berdai et al. (2012) reported a case of belladonna intoxication in an 11-year-old girl who received belladonna as remedy supposedly for her jaundice and who eventually manifested central anticholinergic syndrome while admitted in an intensive care unit. The girl manifested dry mouth, confusion, incoherent speech, uncontrollable vomiting, visual disturbances, and hearing and visual hallucinations. [2] A 2003 analysis involving 49 children suffering from acute belladonna intoxication noted the following as the most frequently observed symptoms: meaningless speech, tachycardia, mydriasis, and flushing. [13]

References:

[1] M. Davies and A. Hollman, "Atropa belladonna," Heart, vol. 88, no. 3, p. 215, 2002. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1767336/

[2] M. A. Berdai, S. Labib, K. Chetouani and M. Harandou, "Atropa belladonna intoxication: a case report," The Pan African Medical Journal, vol. 11, p. 72, 2012. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3361210/

[3] "Atropa belladonna: Belladonna," Encyclopedia of Life, [Online]. https://eol.org/pages/581107/overview

[4] A. Hofmann and R. E. Schultes, Plants of the Gods: Origins of Hallucinogenic Use, New York: Van der Marck Editions, 1987.

[5] C. Ulbricht, E. Basch, P. Hammerness, M. Vora, J. Wylie, Jr. and J. Woods, "An evidence-based systematic review of belladonna by the natural standard research collaboration," Journal of Herbal Pharmacotherapy, vol. 4, no. 4, p. 61–90, 2004. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/J157v04n04_06

[6] "Belladonna Alkaloids and Phenobarbital (Oral route)," PubMed Health, 1 July 2017. [Online]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmedhealth/PMHT0014315/?report=details

[7] Committee for Veterinary Medicinal Products, "Atropa belladonna: Summary Report," The European Agency for the Evaluation of Medicinal Products, London, 1998. https://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Maximum_Residue_Limits_-_Report/2009/11/WC500010731.pdf

[8] C. Raetsch, The Encyclopedia of Psychoactive Plants: Ethnopharmacology and Its Applications, USA: Park Street Press, 2005.

[9] P. Gál, T. Toporcer, T. Grendel, Z. Vidová, et al., "Effect of Atropa belladonna L. on skin wound healing: biomechanical and histological study in rats and in vitro study in keratinocytes, 3T3 fibroblasts, and human umbilical vein endothelial cells," Wound Repair and Regeneration, vol. 17, no. 3, p. 378–386, 2009. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19660046

[10] I. D. Passos and M. Mironidou-Tzouveleki, "Hallucinogenic Plants in the Mediterranean Countries," in Neuropathology of Drug Addictions and Substance Misuse, Massachusetts, Academic Press, 2016.

[11] G. Das, "Therapeutic review. Cardiac effects of atropine in man: an update," International Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, Therapy, and Toxicology, vol. 27, no. 10, p. 473–477, 1989. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2684867

[12] A. Grzybowski, A. Armesto, M. Szwajkowska and et al., "The role of atropine eye drops in myopia control," Current Pharmaceutical Design, vol. 21, no. 32, p. 4718–4730, 2015. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26350533

[13] H. Caksen, D. Odabaş, S. Akbayram, et al., "Deadly nightshade (Atropa belladonna) intoxication: an analysis of 49 children," Human & Experimental Toxicology, vol. 22, no. 12, p. 665–668, 2003. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14992329

Article researched and created by Dan Ablir .

© herbshealthhappiness.com

1. Famous Chef Sheds 60lbs Researching New Paleo Recipes: Get The Cookbook FREE Here

2. #1 muscle that eliminates joint and back pain, anxiety and looking fat

3. Drink THIS first thing in the morning (3 major benefits)

4. [PROOF] Reverse Diabetes with a "Pancreas Jumpstart"

5. Why Some People LOOK Fat that Aren't

6. Amazing Secret Techniques To Protect Your Home From Thieves, Looters And Thugs

7. The #1 WORST food that CAUSES Faster Aging (beware -- Are you eating this?)

If you enjoyed this page: