Butterbur

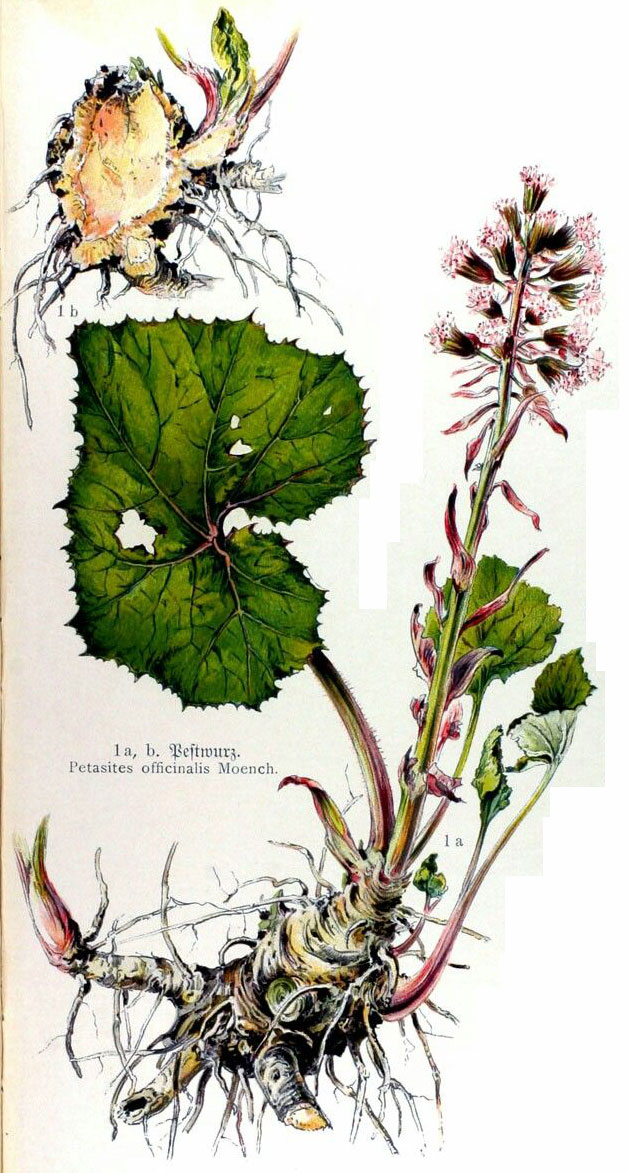

Butterbur (Petasites officinalis)(PD)

Butterbur - Botany And History

Butterbur is a small plant which has been employed since ancient times as medicine. While commonly believed to be a singular variety of plant, it in fact constitutes a wide array of different varietals all under the family Asteraceae, and are collectively referred to by their genus Petasites. Butterburs, so called due to the old European custom of wrapping butter in its leaves during the summertime to prevent melting, comprise a broad range of species, some of which are employed chiefly for medicine, while others are relatively used as ornamental plant, and may or might not have any specific history of medicinal usage. Aside from being a somewhat sizeable genera of plants in its own right, butterburs are also related to many species of coltsfoot (genus Tussilago), and the even larger genus Senecio (which features plant like groundsels or ragworts). Because of its close relation to the following plants, butterbur possesses some similar medicinal properties to coltsfoot and ragworts, although it can stand alone as a medicinal plant with specific properties and uses in its own right. [1]

Butterburs, in spite of their broad genera, is characterised chiefly by its inflorescence, which is the most telling feature of the plant. It is unique in that it flowers prior to the emergence of its leaves, and at first glance resembles a queer seeming hybridisation of broccoli and kale. It is notable for its elongated basal bracts of a green to yellow-green hue, which supports clusters of dull-white or flesh-coloured florets with pink-hued tips. Butterburs are usually hard to grow domestically, even in the most advanced of gardens due to their preference for moist environments and for a near exacting constituent of loamy-sandy soil. Hybridised varietals are more often employed for ornamental purposes, as it tends to be more adaptable to different soil conditions, if it is watered on a regular basis. Butterburs that are employed medicinally are often wild-crafted, with the herb being gathered in rivers, ponds, or moderately large bodies of freshwater where it often grows prolifically. Butterburs may even grow in places such as marshlands and both natural and man-made ditches, provided that ample moisture and the right kind of temperate weather conditions are met in order for it to thrive. When butterbur does thrive, it grows to quite a significant size, with the leaves of the plant reportedly growing to about the length and width of a small coffee table if left to its own devices. Because of the relatively large size of its leaves, it makes for excellent cover for plants that grow best in the shade, and have been used since ancient times as a sort of wrapper for various foodstuffs. Folklore suggests that it may have even been used as a type of headgear (i. e. a woven cap made of its leaves, or a sort of umbrella crafted from large butterbur leaves), although the possibility for this is largely anecdotal. [2]

With the growing demand for medicinal-grade butterbur products, there are nurseries which specialise in the rearing of wild-crafted and transplanted butterburs, which are then bred with other strains or otherwise cultivated in controlled conditions, and later harvested for processing, although such nurseries are small in number.

Butterbur has a long-standing reputation for being a medicinal herb, with the earliest usage of the plant dating back (within the context of recorded history) to before the European conquest of the Americas, although a strong possibility of usage dating back to ancient times is highly possible. Considering its popularity throughout much of Europe and the Americas, as well as the mention of (or description) the plant being extant in early Western and Eastern medicinal texts, the use of butterbur may have dated back to pre-Christian times. In the West, butterburs are typically a favourite medicinal herb of Europeans who dwell in the lowland countries, although it is a far more popular herb in the Americas, where it has been used by the indigenous population since prior to the Colonisation. [3]

Butterbur - Herbal Uses

Butterbur has long been employed as a medicine by a number of civilisations throughout the centuries, although it is most popular in the Western hemisphere than it is in the East, although mention of its employment in Asiatic systems of traditional medicine such as Traditional Chinese Medicine, Japanese kampo, and Ayurveda do exist. Butterbur is generally employed as an all-around analgesic, with a reputation for being an excellent pain-reliever that can be traced back to the earliest of Western herbals. As with many herbs with long-standing usage, the whole of the plant is employed medicinally with specific parts oftentimes employed as a remedy for specified ailments. In more modern applications however, the roots of the plant are far more favoured, although traditionally, the roots, leaves, bulbs, and even the flowers of the plant have been used and processed into medicine. [4]

Prior to the advent of modern herbal medicine, the use of butterbur was strictly restricted to expert herbalists, chiefly because possessed minor toxicity which manifested itself when the herb was improperly prepared or otherwise consumed in excess. The whole plant contains chemical compounds known as pyrrolizidine alkaloids (PA), which are known toxins that can damage the liver, lungs, kidneys, and the circulatory system. While the whole of the plant may be used in either its dry or fresh form, the bulbs and roots were more often dried, while the leaves and flowers were infused or decocted in either fresh or dried form. Because very potent preparations of butterbur were more detrimental to health than helpful, only very small amounts of the plant were used, and the leaves and / or flowers were more favoured for 'mild' remedies, while the roots and bulb were reserved for the treatment of more severe ailments, as the latter was believed to possess far greater potency. [5]

Butterbur was generally infused or decocted into a tisane and given for the remedy of headaches, muscular aches and pains, arthritis, and rheumatism. It was a highly-prized general analgesic, although it was used only in very limited amounts. Because there was very little understanding about the toxicity of the herb, it was employed both topically and orally during ancient times until well into the middle of the Industrial Period (something which is now strongly discouraged, with the exception of employing known pyrrolizidine alkaloid-free strains), with is popularity somewhat declining well into the advent of the Second World War, primarily due to the arrival of better analgesics, and secondly, due to the number of adverse effects that came about from prolonged or abusive consumption of herbal preparations containing the plant-matter. Before its somewhat prolonged decline, it was employed as a remedy for a number of other ailments, with mild infusions or decoctions of the flowers and leaf being given as a remedy for colic, stomach upset, indigestion, ulcers, and migraine, while moderately strong decoctions were employed as a cure for everything from whooping coughs, anxiety, insomnia, asthma, paranoia, tremors, and (in the Middle Ages until well into the Renaissance) even the plague. [6] When employed for the latter, the root, bulbs, or leaves (or all of the constituent parts) were often steeped or boiled in mulled wine and drunk in wineglassfuls some four to five times in day. It was believed to help drive out infection by acting as a diaphoretic, and as a stimulant. Moderately strong to mild infusions in wine were given as an antipyretic, while weak infusions were drunk regularly for its perceived tonifying properties, which was believed by the ancients to help improve heart health and overall circulation (something that, due to the plant's inherent toxicity, is actually contrary to the truth). [7]

Aside from the staple preparations of infusions and decoctions, the whole of the plant was also tinctured, although by the early to latter part of the Victorian Era, tinctures of butterbur were often exclusively made from the bulb and / or roots solely. Tinctures of butterbur were employed to both whet the appetite and aid in digestion, although its most common applications were as a remedy for anxiety, distemper, restlessness, tremors, palsy, allergies, and (of course) headaches. [8] Tinctures were often made in highly concentrated doses, and were strongly diluted with water prior to consumption, both to reduce the unpleasantness of its taste, as well as to cut back on the side effects elicited by the preparation. In more rustic settings, where tincturing was often expensive and impractical, butterbur leaves, flowers, bulbs, and root were often allowed to macerate in cheap wine (or some other similar cheap alcoholic beverage, usually gin) and employed in a like manner, although it was more commonly mixed into spiced wine or mulled cider and drank as a medicine in much the same vein as hippocras. Wine, ale, or cider which was infused with butterbur was given as a remedy for a number of diseases, although it was more popular as a remedy for asthma, bronchitis, flu, whooping cough, and other bronchial disorders. [10]

Prior to the Industrial Period, butterburs were even employed as prime material for the creation of poultices, and the leaves or bulbs of the plant were often ground up or crushed (in fresh or dry form) and mixed with other herbs to alleviate the discomforts brought about by arthritis, rheumatism, gout, and even to hasten the healing of fractures. [11] The leaves of the plant can be crushed and applied directly to the forehead to alleviate headaches, migraines, and nasal congestion, while the dried bulbs may be allowed to macerate in oil, or are otherwise steeped in heated oil, the subsequent concoction then being used as a salve for general pain relief, or as a topical antihistaminic. [12]

While the medicinal uses of butterbur somewhat declined by the time of the Second World War, a slow but steady revival came about sometime in the early 1980s until well into the present day, chiefly due the increased availability of PA-free extracts and strains. Nowadays, butterbur is a popular alternative remedy for recurring migraines and headaches, although its employment for asthma, bronchitis, anxiety, and other such illnesses have now dwindled. PA-free butterbur extracts are available from nearly every alternative medicine shop or herbal apothecary, and come in capsule, tablet, or extract, or tincture form. Because of the growing knowledge of the dangers of non-PA-free butterbur, wildcrafted strains are now only rarely employed by herbalists, although cultured PA-free strains are used in much the same way as wild strains were once used.

Butterbur - Esoteric Uses

In spite of its long-standing use as medicine, butterbur only has a few esoteric uses, although whether due to its somewhat limited area

of notoriety, or due to other reasons well beyond the record of modern folklorists and herbalists, it has only been mentioned as a

divinatory herb in some herbals. Butterbur is not known to possess any hallucinogenic compounds which may suggest some degree of divinatory

application, but rather, it was believed and taught by cunning-folk that the herb was viable for use. It was said that the seeds of

butterbur were to be sown by a young maid (unmarried woman) in a secluded place half an hour before sunrise on a Friday morning. The

following incantation was said to have activated the spell:

I sow, I sow!

Then, my own dear,

Come here, come here,

And mow and mow!

It was said that the woman's future husband would appear sowing from a distance. The caster was adjured that the slightest sense of fear or

uncertainty would cause the vision to de-materialise. [13] Further folkloric practice often employed the leaves and roots of the

plant in a draught of wine, which was drunk ritualistically prior to sleep in order to elicit prophetic dreams. [14] Aside from

such purposes, no other known magickal usage has been ascribed to the plant, although the medicinal attributes of it were, for the time,

considered wholly magickal.

Butterbur - Contraindications And Safety

Because butterbur contains pyrrolizidine alkaloids, the use of non-PA-free butterbur extracts or preparations is dangerous, and is not advised. Non-PA free butterbur is hepatotoxic, and may cause poisoning of the liver if taken in excess or for prolonged periods. Non-PA-free butterbur may also pose risks for the lungs, the circulatory system, and even the skin. Recent studies have shown that the pyrrolizidine alkaloids in wild butterbur are carcinogenic, and may even pose dangers even via topical application.

PA-free butterbur extracts and strains on the other hand are considered relatively safe, although they may react with drugs that help the liver metabolise. It is advised that individuals who take such medication steer clear of butterbur extracts, and avoid using synthetic medication alongside butterbur or any such extracts containing the plant matter. One should note that even PA-free butterbur may not be well-tolerated, as it can cause mild headaches, nausea, itchy eyes, upset stomach, drowsiness, diarrhoea, fatigue, and drowsiness if consumed in large doses over a short period of time, or in small dosages for prolonged periods exceeding four months. Individuals who are also allergic to ragweed, marigolds, daisies and other related herbs are also advised to avoid butterbur. As a general rule of thumb, pregnant and nursing mothers are advised to avoid the consumption of butterbur and all such medicines containing the plant. Furthermore, children below seven years of age should not be given butterbur in whatever form, whether topically or orally. If employed to treat children's diseases, it should be given in very minute doses of weak to mild infusions or decoctions for a duration of no more than one or two weeks.

Butterbur - Other Names, Past and Present

Chinese: kuandong

Japanese: fuki

Korean: meowi

French: chapeliere / feuille de petasite / fleur de petasite / herbe aux Teigneux / petasite du

Japon / petasite vulgaire / racine de petasite

German: pestilenzenwurt (lit. 'herb of pestilence', in that it was useful as a remedy for pestilence, and not

that it caused it)

Spanish: contra-peste / contre-peste

Italian: hierba a la peste / farfaraccio

English: butterbur / bog rhubarb / bogshors / butter bur / butterburr / butter-dock / blatterdock / butterfly dock / capdockin /

exwort / grand bonnet / Japanese butterbur / langwort / plague root / purple butterbur

Latin (scientific nomenclature): Petasites vulgaris / Petasites officinalis / japonicus / Tussilago hybrida (other

nomenclatures exist)

References:

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Petasites

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Petasites_hybridus

[3-4] https://nccam.nih.gov/health/butterbur

[5][6][7] https://www.webmd.com/vitamins-supplements/ingredientmono-649-BUTTERBUR

[8][9][10] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15623680

[11] https://www.botanical.com/botanical/mgmh/b/butbur96.html

[12] https://www.anniesremedy.com/herb_detail235.php

[13] https://www.thewhitegoddess.co.uk/herborium/butterbur.asp

Main article researched and created by Alexander Leonhardt.

© herbshealthhappiness.com

1. Famous Chef Sheds 60lbs Researching New Paleo Recipes: Get The Cookbook FREE Here

2. #1 muscle that eliminates joint and back pain, anxiety and looking fat

3. Drink THIS first thing in the morning (3 major benefits)

4. [PROOF] Reverse Diabetes with a "Pancreas Jumpstart"

5. Why Some People LOOK Fat that Aren't

6. Amazing Secret Techniques To Protect Your Home From Thieves, Looters And Thugs

7. The #1 WORST food that CAUSES Faster Aging (beware -- Are you eating this?)

If you enjoyed this page: